Theodore Roosevelt once said, “The more you know about the past, the better prepared you are for the future.”

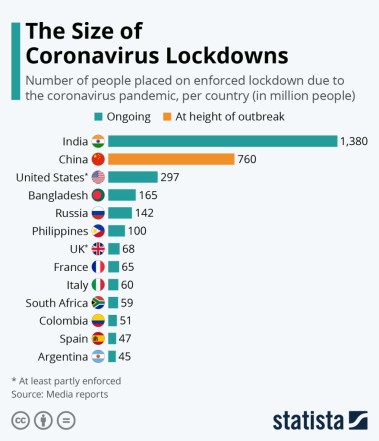

The Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has created a moral crisis for policy-makers struggling to choose between “lives” and “livelihoods”, “mortality or poverty” i.e. between mitigating the public health fallout and averting an economic depression.

This article is about an awful choice we face in light of the COVID-19 pandemic: Should we risk the lives of millions of people by reopening economies too soon or risk the livelihood of millions by opening the economy too late? Any choices that are made will be in the context of multiple unknowns about the virus itself and about restarting an economy that was shut down because of a worldwide natural disaster. There will be great suffering either way.

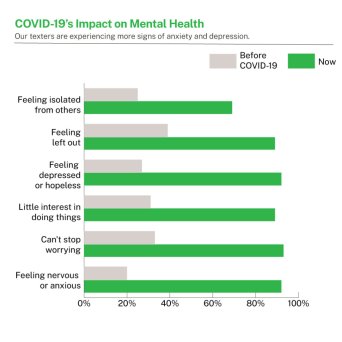

Mental Health

There is a research model going around that suggests as many as 150,000 additional people could die from mental health-related outcomes of COVID-19, in the United States alone!

Mental health is a major part of how we live our lives. When a person’s mental health is good, they can usually cope with and bounce back from whatever life throws at them. But when mental health is poor, it can be difficult to function day to day and it may take longer to recover. Protecting and strengthening the mental health of people (especially the vulnerable ones) is more critical now than ever.

COVID-19 will impact mental health in two phases

One can consider the impact of the pandemic on mental health in two phases: The first is the acute phase, which coincided with the lockdown—the period when the pandemic surged through countries. The second phase will unfold in the months ahead, as the virus starts to get contained, but the economic fallout of the pandemic begins to bite deeper (this has already started to unravel).

Right now, in the midst of the acute phase, people are terrified of the virus, of dying, or of loved ones contracting this disease. They are also scared of being quarantined, maintaining physical distancing, being isolated, and breaking the constantly changing rules. For millions, these fears only add to the already daunting apprehensions about their livelihoods. These are not abstract anxieties; these are real, everyday worries.

If one considers all these factors, and adds to them the increase in domestic violence, the disruption of public transportation, the lack of access to routine health services, and the shortage of medical supplies, it seems almost normative that people are going to be very distressed during this period.

The Numbers

Over the last six months, the COVID-19 pandemic has generated massive losses in well-being around the world – through greater mortality, widespread suffering, higher unemployment and rising poverty.

- Estimates of between 25% to 33% of the community are experiencing high levels of worry and anxiety during COVID-19 (Black Dog Institute).

- Estimates of a 14% drop in global working hours in Q2, 2020; this is equivalent of 400 million full-time job losses globally (International Labour Organisation).

- In April more than 122 million people lost their jobs in India; up to 20.5 million Americans lost jobs at this time; up to 59 Million Jobs Are at Risk in the EU.

- In 2008, the Great Recession ushered in a 13 percent increase in suicides attributable to unemployment with over 46,000 lives lost due to unemployment and income inequality in that year alone. The unemployed are 2–3 times more likely to die by suicide compared to those who are employed (Haw C, Hawton K, Gunnell D, Platt S).

The Social Cost of a person becoming infected with COVID-19

The “statistical value of life,” reflects how much people are willing to pay to reduce their risk of death – for example, by buying safety equipment such as airbags, or how much they must be compensated to work in jobs that involve a small risk of death. In the U.S., a common “statistical value of life” is around $10 million. Research done by Korinek and Bethune multiplied the risk of death from COVID-19 with the value of a statistical life, to obtain the “statistical cost of COVID” in terms of mortality risk.

When they looked at what overall cost it imposes on an individual to become infected, they needed to consider a potential benefit: once the person recovers, they may no longer need to worry about the disease and they may no longer need to distance, which is an economic benefit. Taking into account all these considerations, they found that the statistical cost of becoming infected is worth the equivalent of $18,000 for an individual.

When we talk about the social cost, we also need to take into account that each individual passes on the disease to others, who will in turn infect more people. Based on that, the true social cost of a person becoming infected with COVID-19 is close to $55,000.

One could say that when the virus was first brought to us, it imposed a social cost of trillions of dollars on us. Now, an additional infection costs more like $55,000. If we as a society had been able to better contain the virus, the cost would have been lower. If we let it spread, the cost will be higher. So, was/is the economic cost of the lockdowns worth it?

Conclusion: Mortality or Poverty?

Which source of welfare loss is dominant: mortality or poverty? No matter what decisions are made, illness and death will continue. Unemployment and financial distress will continue. Tens of millions of people will continue to suffer, albeit some will suffer more or in different ways than others.

The coronavirus crisis has made clear just how inextricable mental health is from physical health. You cannot talk about a lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) without talking about the mental health repercussions, and you cannot talk about patients who are dying of COVID-19 without talking about grief. You also cannot talk about unemployment or social isolation without talking about anxiety and depression.

By examining the behavioral health impact of the Great Recession and other large-scale disasters, we can mitigate the negative impact to society from further economic loss and human suffering. Instead of looking at the post-COVID-19 mental health future through a lens of doom, we can, and should, use this moment as the push for changes and destigmatisation that mental health has always needed.